Cost-Plus Pricing

What it is

Cost-plus pricing is the simplest approach to pricing, which is why it’s both loved and hated among pricing experts. For cost-plus pricing, you simply set the sale price by adding a fixed markup to the cost of goods sold.

When to use it

Cost-plus pricing is best used for products with stable supplier and ingredient costs or lower-cost items with high stock rotation. If you sell unique items (e.g., homemade deli items) and don’t have something to compare them to, cost-plus pricing is a good way to test the waters and see how they perform.

Cost-plus pricing isn’t a great long-term strategy for many items. While you’re guaranteed a profit, you might undervalue products that customers are willing to pay more for. This method also ignores swings in demand, supply chain disruption, or competitors’ pricing.

How to use it

Cost-plus pricing is easy to calculate. For example, if you get bags of of chips from a supplier for $2.50 a bag and want to apply a 70% markup, you’ll sell them for $4.25.

$2.50 x (1 + 0.70) = $4.25

Competitive Pricing

What it is

Competitive pricing is when you set prices based on your rival businesses. While many companies use this tactic to bring customers into their store with low prices, competitive pricing isn’t always about being the cheapest. If you offer high-quality local food, you may use a competitive pricing strategy to raise your prices instead.

When to use it

Competitive pricing is often used in the grocery and supermarket industry because many stores carry similar products. Competitive pricing is helpful because it helps you set benchmarks based on other businesses. It also ensures you don’t drastically under or overvalue your products.

How to use it

Start by identifying your local competitors and doing some market research. Consider things like:

- How the quality of your products compare to competitors

- How customers perceive your brand

- How much demand there is for particular items

- What the local market rates are for certain products

You can also use third-party services like UNFI to assess prices on an industry-wide or regional scale.

When implementing competitive pricing, have a clear and quantifiable goal in mind. Last, remember that while customers are looking for the best deal, that doesn’t always mean having the lowest price tag — so be creative with product bundles and other promotions.

Loss Leader Pricing

What it is

A loss leader is a product that sells for less than its cost in order to sell other, more profitable products and drive foot traffic. Here are some common examples of grocery store loss leaders:

- Whole rotisserie chickens at lower prices

- Offering free flu shots with a $20 grocery discount

- Selling bags of rice for a few dollars apiece

- 50% discounts on Fridays on ready meals or select items

Items could either be consistently kept at a low price or temporarily made a loss leader as part of a product bundle or promotion.

When to use it

Loss leaders are commonly used in grocery stores because people rarely go into a store for just one item. By selling a few products at a loss, your brand seems more affordable, and it encourages customers to take advantage of the savings by buying other products in the store.

For most grocery stores, loss leaders are used for short-term promotions. Companies like Costco can afford to keep selling their famously cheap $1.50 hot dog and other items for years on end because their business model involves membership fees and large purchases that more than make up for the cost.

How to use it

Implementing a loss leader strategy requires carefully reviewing your products and looking for items with high demand or ones that naturally lead to other purchases. In other words, you don’t want to sell products at a loss if customers aren’t likely to buy anything else.

Start by trying out a loss leader strategy as part of a holiday sale or planned promotional event, then use the sales data on your point of sale (POS) system to see how it affected average cart size and sales.

Variable and Seasonal Pricing

What it is

Pricing in supermarkets is tricky because produce and many other food items are highly seasonal, perishable, and fluctuate in demand. Variable pricing, also known as dynamic pricing, is when retailers adjust the margins on individual products based on:

- Seasonality

- Local demand

- Product freshness

When to use it

Variable pricing is most often implemented in grocery stores to help cut down on food waste and ensure that in-season fruits and vegetables don’t spoil. One common example is when items close to their expiration date get discounted.

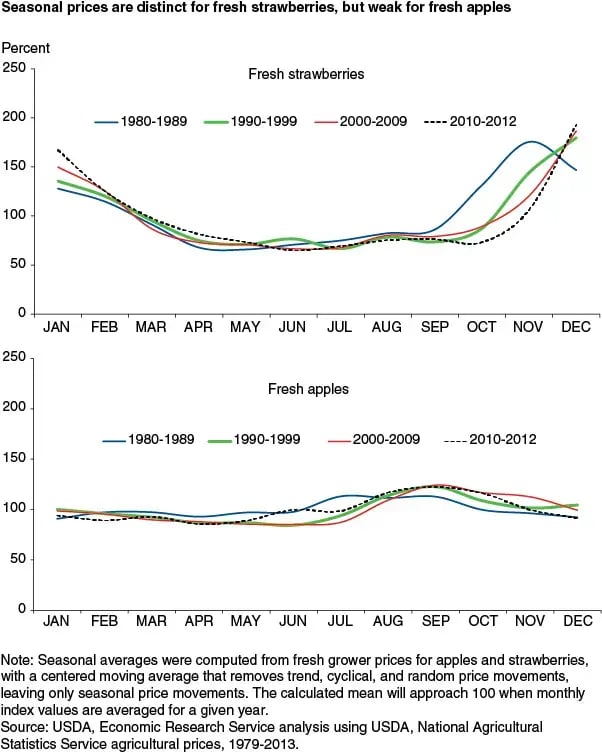

Produce prices, in particular, fluctuate throughout the year. Generally speaking, produce has an inverse price to freshness pricing, with lower prices reflecting fresher produce since there’s a higher supply and lower transport costs.

Source: USDA

Variable pricing can also be used to account for seasonal fluctuations, like pricing potatoes, bread, and other high-demand items more competitively around Thanksgiving.

How to use it

While some larger brands are experimenting with electronic shelf labels (ESLs) that allow them to change prices dynamically throughout the day, you can proactively implement variable pricing on a less granular scale.

Use the historical sales data on your grocery POS system to spot seasonal sales spikes and drop-offs in different departments. This will help you understand which products customers are willing to pay more for in high-demand times and which items they might go to a competitor for instead.

Psychological Pricing

What it is

Psychological pricing isn’t a specific pricing strategy, but a tactic that supplements others. It specifically refers to how prices are written out and formatted, and how it affects customer attitudes.

The classic example of psychological pricing is the power of the “.99” at the end of a price. Research backs up what many of us have instinctively felt: buying something at $4.99 simply feels different than buying it at $5.00.

Here are a few other common tactics used in grocery stores:

- Left digit bias: Stores tend to make more sales when prices end in “99” instead of rounding up because people perceive value based on the leftmost digit in a number.

- Center stage: When presented with three similar products and services at increasing price points, many people pick the middle option. This can be useful to keep in mind when laying out products on shelves.

- Innumeracy: Sometimes, how a deal is worded affects how people perceive it. For example, one study found that sales increased when stores labeled a deal as “buy two items at 50% off” versus “buy one get one free” (despite giving customers the same value).

- Formatting: People tend to perceive longer prices as more expensive. They’re more likely to buy something marked at “$15” versus “$15.00” with the extra two digits.

When to use it

To a certain extent, you’ll always be using psychological pricing, but it’s not something you should do at random. Supermarkets are constantly adjusting prices by small amounts to provide customers a better sense of value.

How to use it

Psychological pricing tactics shouldn’t be used randomly. If you constantly change how you display prices, people will catch on and lose trust in your brand. Like all pricing strategies, have a specific goal in mind when making changes, and monitor their effectiveness using your POS system.

Try to think of how certain price points affect the perception of an item. Does placing an item next to others make it seem like a value or premium product? Does dropping the price below a certain number make it seem like a better deal?